A personal reflection of growing up in L.A.

Being in a state of prayer and purpose on Monday at Pastor Jean-Marie Cue’s “Where do we go from here?” interfaith memorial for the mass shooting victims in Buffalo, Laguna Hills, and Uvalde, I found myself questioning how has violence shaped my own life and identity, and how am I contributing to its continuation? The response came through this elongated essay recounting my personal experience from childhood in 1975 until approximately 1995 when I graduated from grad school. During this journey I learned to navigate multiple forms of violence including community, racial, and global. Interconnecting all is a white supremist, patriarchal practice of capitalism.

I can’t recall my first experience with guns or gun violence. I grew up around gangs during the 1970’s, crossing Bloods and Crip territories between my house in Inglewood and my babysitter’s house over on 39th St. off Normandie. Over there everyone, including me, feared my “cousin” Tee. The entire street was our playground and when we would go out of bounds – like going pass 3 to 4 houses, the apartment building across the street, or heaven-forbid turning the corner- and saw Tee, we ran faster than if we saw my Mom. There was a code of the street and respect for where one called home and for the safety of children. While there were always stories of a gun used in a robbery, in those days the boys just fought – fist to jaws, stomach, or chest. A dirty fight was when other jumped in and on occasion someone pulled out a knife.

I learned from watching the boys the culture of “heart” – of being always prepared to fight. For whatever reason, initial running was never an option. You could “wolf,” you could dance and not throw the first punch, you could get beat up, you could use anything as a weapon if you were losing, but you could not run. I also learned the vulnerable places where one could be jumped – walking around the corner and school bathroom stalls – so always be prepared.

I internalized this culture. As a girl, my first act of violence against another person was a classmate around the age of 6. A girl I barely knew was taunting me on the playground and I told her to leave me alone. She didn’t, so I kicked her in the stomach. I didn’t feel good afterwards and probably cried more than she did when I got home. The vibration of my contact to her felt icky. Later, on the school yard a few years later around the age of 8, while in the cafeteria line waiting for lunch, I was challenged by “my friends” to see if I had “heart”. To pass this rite, you had to stomp up, roll your body into the face of your opponent (eyes and neck did their own roll), and prepare your right fist to swing, just in case the person pushed or swung back. I think my friends were surprised I knew the ritual, and all fell out laughing with nods of respect– I was in.

After this experience, I was bussed from South L.A. to the Valley and had to learn how to fight racism – not through my body, but through my mind in balance with remembering myself. I had to adopt to new rules such as lining up for everything – To go inside the classroom, to go outside for recess, to sit down for lunch, to come inside, to go to the bathroom, to check-out a ball, to check-in a ball, and to get on the school bus to go back home. I actually got written up for cutting the line to return my ball after lunch one day, as I feared being late to class more. I also experienced for the first time a White person, our teacher, thinking that we were “less-than” based on where we were from and of course the color of our skin. While Mr. Vaughan was the best math teacher I ever would have, I never forgot how he made me feel.

For the fourth grade, I transferred to another school in the Valley where my mom worked. Most of the teachers were Jewish and leaned “left.” However, things were different among the students. When we were all out on the playground, it felt like there was a fair representative of Black students, however inside the classroom, there was only 1 to 2 of us. Consequently, “friends” became those who you spent the most time with and most of my friends were thus white. This was the closest moment in my life where I was able to pierce the veil of wealth and class culture. It was vicious and often made me question my own sense of self as I compared myself to those around me. When I first arrived, my mom made sure that I knew the Black students, most of whom were older than me, and they would check on me during lunch breaks. Students of all races spoke with one another in class and in the hallways, but students tended to stick to each other by geography and this was a proxy of race.

The upper-income Valley kids hung out together, the Canoga Park kids hung together, and students bussed in from L.A. tended to hang out together. I was kind of in no-man’s land by being the daughter of a school administrator. In this space, I quickly learned the violence of “cliques” and “mean-girl” culture. In the circle of my White classmates, words like “stuck-up,” “snob,” and “ho” were flung around like daggers and someone for whom we were all friends with the day before, suddenly were banished from the clique and the fear of also being banished by association re-enforced the marginalization of the person. It was vicious because the ruptures seemed spontaneous. It also erased intimacy among friends because you never knew who was going to turn against you. At my home school, I realized our rituals were tests to see who would have your back.

Here, I didn’t trust that anyone would. In fact, I began to feel more and more isolated. Among my white “friends” my difference was noticed through round-about comments and eerie desires to touch different parts of my body: “are you legs really that brown or are you wearing stockings?” “Can I touch your hair? It is different than most Black girls.” “What are you? You can’t be all Black” “You are so tall; your parents must be tall.” In these exchanges I learned the meaning of light-skin privilege because I noticed that we did not hang out with my darker skin classmates at lunch, nor were they invited to birthday parties and weekend sleepovers. As Black girls we would try to hang out, but I think the daily survival in a white world prevented us from getting close or building authentic relationships. Recently I ran into a Black classmate from this period, and she absolutely did not remember me. She had even spent the night at my house for a graduation party sleep-over. It made me sad. At an age where children start to develop crushes, I noticed that white boys did not find me attractive, and the Black boys thought I was stuck-up because I hung out with white girls. I could not win.

In this school environment, I began to learn the subtle differences of class among white folks. I was paired with a group for a science project. We went to one of my classmate’s homes after-school to work on the project because her mom did not work and was home to help us. She lived in an upper-income neighborhood in the West Valley. The assignment was to protect an egg from breaking, so we went to the second story of her home with our concoction to drop it from the second-floor balcony off of the “playroom.” I could not fathom a whole room dedicated to my classroom and her siblings – not to sleep, but simply play. When I got home that evening and looked around our 2-bedroom home, which was nice and even had a pool, I felt different. I felt ashamed. My refuge during these years became my dance and drama teacher, an African American woman – Mrs. Greer. Inside of the characters from the Wiz and Oliver Twist – I was able to just be me.

Shortly after this moment, on a trip to Ensenada, in Baja California, Mexico, the memory of my classmate’s playroom made me think that the brightly colored tiny homes along the hillside were dedicated to children. I remember saying something to my Mom like “I wish I lived here so I could have my own house to play.” My mom looked at me confused and asked me to explain more. She then understood and then shared that those were not homes for children, but entire families who were poor.

I re-entered the Black world for junior high school when my mom remarried, and we moved to Pasadena. There was a lot going on in our home with the merging of two families, so school became a refuge. Our school was diverse, and I found the greatest sense of safety and acceptance among other Black students. We could talk without needing cultural translation. Among my new friends, my identity was never questioned, instead I was just “thick,” “redbone” and had “good hair.” While these cultural expressions of Blackness were understood, I remembered the lesson from my former school that these were also considered privileges in our social-cultural hierarchy that placed me in closer proximity to whiteness. The older girls and my step-siblings- who had only gone to private schools – thought that these features could be vulnerabilities that may get me jumped, so I learned how to always be ready to fight; carrying a box cutter under my sleeve when I had to go to the bathroom during class, a rubber band around my wrist in case I needed to pull my hair up into a ball, and earrings that could quickly slide off. I soon learned that most girls fought over boys, so tried to get the full scoop on anyone that I was attracted to or was attracted to me before “talking.” I also just practiced being humble and cool with most folks.

Thankfully I never had a fight in jr. high or high school, and to think of it, most of my friends did not fight either, maybe an argument, but not a fight. We had a sense of pride of being from the same school – like kin. We also had other outlets to work through competition and find purpose like sports, drill team, the Girls Club, Salvation Army Basketball League, summer camps, parents (that many of us were afraid of), and morning bagging sessions.

The summer after my first year in junior high school, the entire region was held in terror by Richard Ramirez- the Night Stalker. To this day I do not sleep with any doors opened and only windows that I know one cannot reach from the street. I will never forget the moment of watching the news the day community folks in South L.A. captured him and beat his behind, holding him down until the police came. We were so terrorized by his killing spree that the death of a popular coach and student were initially thought to be victims of the Night Stalker, until it was found out they were killed by another student as allegations of sexual molestation began to surface. At that time, white coaches provided alternatives for youth, particularly boys from going into the system – but no one ever spoke about the potential of abuse and exploitation given the racial/class/age/gender power hierarchy in some of these situations. This truth was hard to talk about as everyone knew of coach, and some guy friends had hung out at “coach’s” house, especially youth going through hard times. To this day, I am not sure there was anyone around to help students process all that had just happened; coach was dead, period. This was a moment that I learned to normalize trauma against Black boys and youth and respond with silence.

While we were processing these specific incidents of violence, we soon were to be immersed in a rising wave of global violence, although it felt local at the time. War in Central America, mostly El Salvador, was continuing to escalate. I remember seeing images of the war on the nightly news, waiting for a favorite t.v. show to come on. At the time, my family lived off a street where a Marine base was located. My bedroom looked over this street and I still remember the fear when the base must have been doing drills or moving equipment and I saw military-style vehicles were advancing down the street. All I could think of was that the “Gorilla War” was near, and we better learn “how to fight.”

This would not have been my first exposure to global violence as most of my childhood was impacted by threats of the Cold War with Russa and the Iran Hostage Crisis that propelled Regan into the Presidency. But this was different. It was real with real bodies showed on the news. I just did not know how close the war was beyond my imagination until I began overhearing classmates share stories of family in El Salvador and in a few cases, becoming fearful when markings were made on family members’ homes here in the States.

Around the same time, other classmates started talking about “rocks” – crack cocaine. Like all generations before us, I and others had already experimented with cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana by junior high, but we looked down on other drugs. Not because of Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign or sizzling egg commercials that alluded to your brain on drugs, but because we all had heard stories of someone sniffing or smoking a joint laced with Angel Dust and trying to fly off a roof or other crazy apparatus and didn’t want to look like a fool. It wasn’t until much later that I began to see the impact of crack cocaine on users of the drugs, but immediately I began to observe the social price of drug sales. Differences among us began to stand out based on dress, what shoes you wore, if you drove a car – Suzuki Jeeps the most popular – had a beeper, and other subtle effects defined by a “cool factor.” Friends became more secretive. I remember showing up at weekend house party and one of my big brothers saw me and firmly told me to go home – I didn’t need to be there. Sure enough, the party ended with someone shooting (no one hit) and the Sheriff’s coming to shut it down. But why did he stay? Soon afterwards we started having a school police officer on campus, locker searches, and then no lockers to reduce storing of drugs on campus.

Community violence began escalating as there suddenly seemed more access to guns. Where in the past you may have heard of a liquor store being stuck up or someone robbed at the bus stop or even a home invasion robbery like the one that killed my dentist Dr. Strong, the use of guns had not been that common. It started afar with threats of drive-bys during away football games, especially as our teams climbed in CIF and we had to play teams across gang and ethnic lines and who won. I was a “manager” on the varsity football team – a glorified taper of stinky athlete’s feet, along with a few friends and we always traveled with the team. A male friend from NCCJ Big Brother/Big Sister Camp attended Gardena. He was the kindest person and had to survive the world around him. I remember it felt like crossing the Berlin Wall to meet at the end-zone during half-time to say hello. The consequences for him being seen with me in my white jersey with red lettering would have been worse for him than for me.

Long-time tensions between Blacks and Mexicans, especially neo-Nazi Mexicans in San Bernardino and different sects of gangs (that would sometime fight each other) were now backed by guns. It was a time of disassociation. Around this time, I was selected onto the swim meet. I remember distinctly a meet against Chino Hills. With all the rumors of Mexican Nazis, I didn’t know what to expect and was a little nervous, although my white team members had no clue. Once in the water though, we were just swimmers. The Chino team was the only all-Brown team that we competed against and after a few laughs and words of encouragement at the start, I remember wanting them to win as they swam their hearts out. It was a moment when I thought it strange that I was taught to fear people that I looked like.

After a major local drug entrepreneur was arrested, it seemed like violence really escalated. I remember when a woman driving down the street was shot and killed while driving. I did not know her, but the impact of thinking about her last moments induced a new fear in me. Later, I started losing people who were closer and closer. First was the boyfriend of a close friend, then the cousin of staff who worked at the Girls Club, and the son on of one of my mom’s friends while sitting at a bus stop in L.A. Violence across the region escalated to epidemic proportions where the L.A. Times began running a series outlining the stress and despair among children who were starting the fear that they would not make it to 18, and had to dream more about their funerals than weddings. Comparisons were also starting to be made about the life span of an American Black Youth with that of men in poor countries with limited healthcare and economic opportunities such as Bangladesh and Haiti.

While we were learning how to straddle a world of “normal life” of sports, activity and cultural clubs, student government, falling in love, Homecoming Queen Elections, Spring Dances, Proms – with increasing violence; relations with law enforcement also escalated. Many of us lived in unincorporated County so were serviced by the Sheriff Department. I had an uncle who was a Sheriff, one of the first high ranking African Americans, however he was honest that racism was rampant in the department. He explained that Sheriff officers were trained in the County Jail before patrol on the streets creating a bias that everyone, especially Black and Brown males, were criminals. They were a normal pain for showing up at house parties first with their helicopters and bright lights (most parties occurred in the back yard), and then lining the streets with all the lights off of their patrol cars, startling us as we piled out of the party. But for others, they were far worse. I remember hearing the painful story from one of my male friends after he was taken up to Angeles Crest Highway and let go after being stopped by the Sheriff. We could not even figure out who could we tell. There were also rumors that it was the Sheriff who started local gang wars by shooting in one area and blaming a rival gang.

In Los Angeles, the police department started deploying militarize weapons including the batteram to knock down doors on “drug” houses, although some were homes of regular folks based on bad intel. Piloting first with LAPD, the federal government began supplying local police departments with military style equipment through grants under the “War on Drugs.” As many have documented, communities, including Black and Latinx communities, were led to support tougher anti-drug and anti-drug trafficking laws including the infamous three strikes law, leading into the era of mass incarceration.

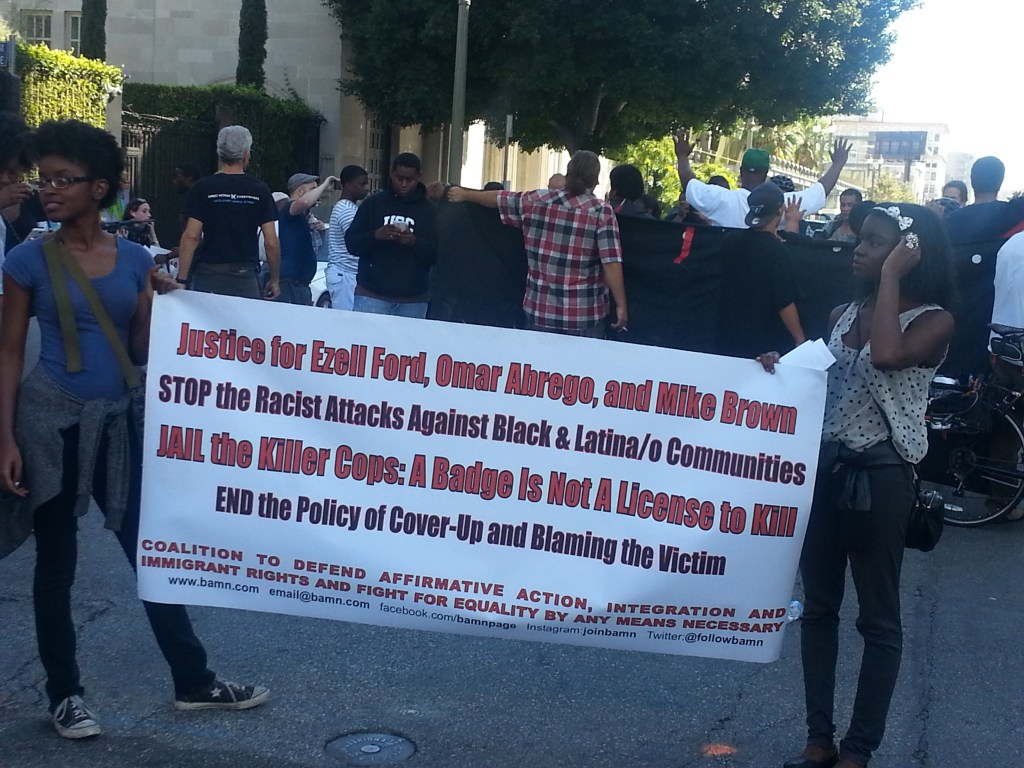

My own interaction with Pasadena Police came when a pair of officers began spraying mace as they walked through a local hamburger hang-out place called Lucky Boys. We had just attended an all-star football game and were gathering as one of the last events before most of else either left for or returned to college. It was actually a quiet night and things were calm with lots of laughter. As the police officers walked by, we all started choking and eyes started burning. We realized what had happened so went up to the officers and asked what they were doing, and they just responded that “it was time to go home.” Thankfully one of my friends got a badge name. My mom gathered our parents at my going away party and invited the NAACP. My party became a testimonial with myself and friends sharing what happened. Afterwards the NAACP and our parents filed a complaint. Through a family member who worked in the department, I heard that discipline action was taken, but this did not always take place. Shortly after attending college, the video of Rodney King being badly beaten by LAPD flooded news stations across the nation giving some form of proof to stories told by Black and Brown communities for years. A few days after the video was released, 15-year-old Latasha Harlins was killed by a local store owner over an allegation that she stole a bottle of orange juice. In the end, neither the police nor the store owner (after being convicted) were held accountable for these crimes leading to the 1992 Civil Unrest.

During high school, Big-Brother/Big-Sister Camp and their Youth Leadership Program sponsored by the National Conference of Christians and Jews (NCCJ) provided a safe refuge while helping us build leadership skills to facilitate life-affirming human relations. My mom supported me as she dropped me off to mee fellow NCCJ staff and participants as we participated in a large protest against Apartheid in front of the South African Embassy in Los Angeles. We intuitively knew there was a stronger connection to what we were going through in the US with our South African Brothers and Sisters so felt we had to stand in solidarity. Through NCCJ, I became part of a team to help build dialogue between Asian and Latinx students in a neighboring school district as gang violence between male members of these communities erupted. With my NCCJ mentor support, I also was selected to serve on the local Youth Advisory Council were we successfully advocated for the Department of Recreation to run a midnight basketball league as a safe place for youth to go overnight. Finally, with the support of NCCJ, I received a scholarship to go to college at Xavier University of Louisiana with a promise to develop programs for Black youth, particularly males as a violence prevention approach. Dr. Antoine M. Garibaldi, Vice President of Academic Affairs at Xavier was writing about the crisis of young Black men at the time at the national level and agreed to oversee my work. I am not naïve to think that these efforts stopped the violence, but they shaped my thinking around the power of community-based alternatives and interventions.

In college, I started to learn more about the interconnectivity between all of the forms of violence I had experienced directly or as a witness by the age of 18; inter-group, community, racism, poverty, war, law enforcement. I went to college at Xavier University of Louisiana, an HBCU in New Orleans, hoping in some ways to be able to decompress from the background noise of community violence. I was told by many that New Orleans did not have gangs and most violence was inter-personal, between people who knew each other and were caught up in love triangles or bad debts, etc. This may have been true, and it was also true that New Orleans was experiencing its own flood of drugs including cocaine and crack and guns. In many HBCU towns around this time, tensions grew between out-of-town students and the local community. Xavier created a number of community engagement activities with the surrounding community to mitigate these tensions, but every now and then at a party, the guys from New York and New Orleans would fight. By our junior year however, the violence escalated. I remember attending a house party when shots rang out inside of the house and my friend pushed me into the fireplace until the shooting stopped and we got out of the house. In all my time in L.A., I had never been that close to a shooting. Later one summer, a mentee was killed execution style after being set-up over drug turf. His death was crushing as I knew when he shifted toward distributing and I never had a conversation with him. In fact, he was the dealer that we all trusted buying weed from. He sold more than weed, however I have had to accept being complicit in his death by staying silent. The only way I could reconcile this was to stop smoking weed, testing other drugs was never of interest. This mentee also came from a wealthy family of professional parents. His story taught me that drugs, guns, violence, etc. were not an issue of class or education or geography, but more related to a toxic culture of “fitting in” and earning respect through death. Too many Black youth were dying at the downside of the global drug supply chain, and I wanted to understand who was feeding drugs and guns to our community? Later Congresswoman Maxine Waters held Congressional hearings exposing the link between Iran-Contra scandal where the US sold guns to Iran while siphoning off funds to support the Contras in Nicaragua who also funded their purchase of weapons through the sell of crack cocaine to dealers in the United States.

College was a time of protest. President Bush (senior) invaded Kuwait in what became the Persian Gulf War. Male classmates who had signed up for the reserves to pay for college, were being called to active duty. We raised up in protest. Not too long after this, David Duke, a white supremist and Grand Wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKKK), ran for Governor of Louisiana. We raised in protest. When policemen were found not guilty in the beating of Rodney King, we marched in protest in solidarity with our Sisters and Brothers in Los Angeles. When Rep. Avery Alexander, an elder Black statement, was placed in a chokehold by Louisiana State Troopers during a protest against David Duke, as student body president at the time I partnered with the student body president from Dillard to hold a press conference denouncing this action on Xavier’s Campus. About an hour before the press conference, the Fruit of Islam from the local mosque showed up – sent by Minister Louis Farrakhan himself for protection. I had not even thought of the potential for retaliation from white supremist organizations. President Francis later shared how Xavier provided hospitality and refuge to the Freedom Riders one summer, in the face of threats from local white supremist. We were continuing a tradition.

We moved through these events with the support of many elders including Baba Dick Gregory, Kwame Ture, Malikah Shabazz, Dr. Ni’am Akbar, and I think Kwanzaa Kunjufu with many others. They helped us put all that was happening in the world into context. I also had the opportunity to intern on Capitol Hill with the late Honorable Mervyn M. Dymally who at the time was the chairman for the Subcommittee on Africa. I learned under fire with support from the Subcommittee staff and Congressional Research Office, in being tasked with developing questions for public hearings about the concepts of terrorism, bilateral and trilateral aid agreements, the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and how to think critically as I read information from a U.S. government perspective. Mr. Dymally was from Trinidad, and he understood structural inequality between the allocation of resources between what we then called the developed world and developing world. He was determined to make sure that myself and my other intern colleagues learned not to read at face value, but how to see in between the lines and identify the true effects of policy on Black and other populations of color. Through this opportunity, I also learned about the Horn of Africa, rising cases of HIV (in some cases transmitted through reusing of immunization needles) and the Southern African drought and its threat to food security across the continent. In looking back, I realize now that the seeds of war and mass migration were sprouting during this time in what has now become a full bloom of climate crisis and human displacement.

After this experience I studied abroad in Kingston, Jamaica the fall semester of my senior year, 1993. Through classes on the campus of the University of the West Indies and an internship with the Kingston Restoration Company, I learned how to see the world from the perspective of the Global South, an experience that I can only relate to what it must feel for astronauts to look back on earth from outer space. I learned new language like US Imperialism and structured adjustment. I had a teacher who was a communist and another who was present during the U.S. invasion of Granada. I was introduced to the Caribbean scholarship of Walter Rodney, Eric Williams, C.L.R. James, Hilary Beckles; writers Jamaica Kincaid, Jean Rhys, and Rex Nettleford (who we met), and even introduced to African American scholars like Derek Bell and Manny Marble.

Through my internship I learned how political parties exploited the poor by feeding gang leaders with guns and cash during the election season for the votes, escalating community violence. I worked with a group of young men from the community. We created a literary arts program focused on writing and centered on storytelling as a form of expression, problem-solving, and goal-setting. In seeking to connect the youth to local professionals who I met while out and about, I learned that internalized prejudices ruptured cross-class collaboration so that no matter how smart one was in school, where they lived determined their education and access to job opportunities. My students also taught me how this community protected one another. One day while walking the few blocks from the main office to the community center where we met, I was robbed. Normally one of the students would meet me but on this morning no one did, and I had been in Kingston a little over a month by now so felt comfortable. While crossing a vacant lot a young man walked up to me and started a friendly conversation. I thought I had seen him before so let my guard down when suddenly he put his hand in his pocket like he had a gun and asked me for my money. I threw a few Jamaican dollars at him and ran to a nearby business yelling – “thief, thief.” The security guard ran out and let me in and then flagged down a car to give me a ride to the center. Once there, the center director noticed that I was shaken so asked what happen. By time I got it out, the young man who robbed me walked down the street. The director then stepped to him, exchanged words and I got my money back. When the students found out, they were upset and wanted to find the person. By the end of the day, one of the local leaders came and asked me to walk with him to find the person as he was upset that people would try and harm a friend. As we were walking, I saw the young man again, but seeing the terror on his face when he saw me walking with this leader, I didn’t say anything. In this space of extreme poverty where people turned up music because the tin walls were so thin; where we shared curried chicken backs and rice and peas for lunch; and where family members had to take food and blankets to incarcerated and hospitalized loved one – a sense of community and belonging existed that I have yet to see in more affluent neighborhoods.

Finally, to round out this experience, following in the footsteps of Mr. Dymally and my dad, who had traveled there about a decade before, I found a way to get to Cuba. It was a time when many faith-leaders risked their freedom to break US law to travel to stand in solidarity with the Cuban people. It was also a time Russia had withdrawn resources with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and food and other scarcity was prevalent to the point the government had to ration all food and basic supplies. Standing in line was part of the norm of navigating the city, even for tourist. I was only there for a weekend, but thankfully we connected we local Cubans so got to see the city of Havana through their eyes and daily experience, a perspective most tourists did not get to see. I left conflicted. On the one hand the people’s pride was so great that collectively they found a way to make it through, sharing even the little with us; and I saw advancements there in healthcare and the way they took care of persons living with AIDS that was much more humane than the stigma and ostracization that I witnessed in the states. Yet, on the other hand I witnesses anti-Black racism as people with brown and darker skin were not allowed to work in the hotels – a policy going back to the US occupation a century earlier; and the stifling of gathering and laughter as more than a few times we ran into military officers patrolling the streets and everyone became somber. Creating a “new path” beyond our democratic capitalist model was complex.

My study abroad experience broke my hymen and gave me a greater perception about the world and the effects of US government and culture’s perpetual hunger for domination and consumption on the lives of non-white land-owning men, worldwide. I returned to the states transformed. I now had a stronger framework in which to see the attitudes, policies, and practices that were negatively impacting Black communities across the U.S. like Los Angeles and New Orleans, but also impacting Black communities around the world like Kingston, Havana, and cities within the Horn and across the Southern Region of Africa. I did not quite know what to do with all of this information. I needed guidance on how to channel these learnings and awakening passion. After speaking to a few people at a graduate school fair on campus, I applied to the University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (Pitt) and was accepted.

My experience at Pitt was another learning inside of a formal academic program. As a majority white school, it was quite different from the nurturing environment of Xavier University and HBCU experience. Whites were also more conservative and patriarchal – men and women – than I experienced at white elementary schools in Los Angeles. By this time the crack cocaine and its negative impact on families, communities, and public safety had emerged into the academic discourse. I will always remember the exact moment in a public policy class as we were discussing HIV and access to healthcare, a white male student blurted out, “if Black women stopped smoking crack and having sex, we would stop the spread of HIV.” How do you respond to that?

Our program was a collective of public administration, public policy, international development, and security studies. People either had been or wanted to go into the Peace Corps or other international development organization like United Nations Development Program, while others the CIA or State Department jobs, and the more practical persons amongst us wanted to work in local or state government. You could imagine our class discussions on the continual fall of Russian currency, invasion of Somalia and Haiti, rebuilding after the Kobe, Japan earthquake, and other global events. We also had a large international student body, many the children of ranking diplomats and government leaders in their own countries, and others as part of U.S. Agency for International Development and other “capacity building” exchanges. This was the first time that I met and had an opportunity to socialize with white Latinos from Central and South America. Their perspectives of me and global issues was very different that mine; conservative, pro-US, and anti-poverty in the sense of criminalizing the behaviors of poor people who were majority Black and Brown in their own countries.

I had one Afro-Nicaraguan classmate who introduce me to the African presence in Central America. Through him I researched and drafted a report on Corn Island, Nicaragua and the communities of African descent who had been marginalized by even the communist government. This place is still on my bucket list to visit. For the most part, I bonded and later lived on a block of student housing with many African and Caribbean immigrants who were graduate students in my program and others across Pitt. There I found community. The men loved to cook and us as women would host study groups and social parties to shake-off the rigorousness and pressure of being in such a competitive and racists academic setting. A friend from Barbados introduced me to the concept of self-care when one day she brought me a stack of paperback romance novels to read instead of the heavy philosophical geopolitical works of Fanon, James, Williams, and others that I was reading and would want to discuss with the whole block. Those books probably saved my life.

Despite our differences, the Oklahoma City bombing bonded us together. I will never forget the day it happened. I was in the administrative office seeing if I could opt out of a class and graduate early when someone turned on a television for a breaking news report. Someone had bombed the Alfred P Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. Over a hundred people died. At first the news media thought it was Middle Eastern terrorists and by the end of the day it was clear that it was done by domestic terrorism, a white supremist named Timothy McVeigh. The one thing we all had in common was a desire to leave Pitt by entering a distinguished career in government. The bombing could have impacted any of our future selves. This was a pivot in our journey. Things got real.

In my 50 years I would go on to witness many more acts of violence in community and the world. During this life journey, I lived through the cultural pivot from social justice movements advancing civil, women, and gay rights to an individualized pursuit that hooks observed as “Americans were asked to sacrifice the vision of freedom, love, and justice and put in its place the worship of materialism and money[1].” Her antidote is the reclamation of love. I agree.

[1] hooks, bell. All about love. William Morrow, New York: NY 2001