This is the written text of my keynote address at the 2026 Annual Santa Monica Area Interfaith Council MLK Breakfast. It is not verbatim as the room at Mt. Olive was filled with spirit and spoke what it wanted in the moment – but these words were written in reverie and offer a jest – acknowledging all of our complicity in our separated/segregated world and our longing to reconnect through love. May these words offer some encouragement and affirmation of what brought you to this site and what you are seeking. Ase’.

I thank my sister Sinaa Greene and her colleague Akinlana Kwesi Williams for carrying the spirit of the drum – ayangulu, and opening the space for spirit to enter.

From the Illusion of Separation to the Practice of Love . . .

Dedicated to the people around the world suffering through the wound of separation that causes othering and devolution of human life.

Elders, Rev. Kathleen Benjamin and Mother Rickie Byars, may I have Permission to begin . . .

Opening Water Libation

- Omi tutu – May water be cool

- Ori tutu – May our heads be cool and open to receive

- Emi tutu – May our hearts and spirits be cool

- Ile tutu – May this space be cool

- Ona tutu – May the road here for those on their way and the road to our homes be cool

- Ase, ase, ase.

I come to this gathering reflecting on my 30 years in the homelessness sector and at a crossroads where I feel the wounds within of surviving through extractive policies and transactional solutions normalizing the lifetime experience of homelessness as personal choice and responsibility or as of charity and an accessory of faith (the poor will always be with us ) – these are false illusions of social hierarchies and separation – that ignore the fragmented economic, social, and spiritual root systems that have produced the landscape of where we are today – longing, desiring, missing – deeper connection to ourselves, our feelings and emotions, one another, to the earth, and the divine essence that is bigger than ourselves. – essentially existentially homeless in a world that feels out of control, divisive, and absence of hope, blinded to the blooming of who and where we are in exercise of our divine right to be.

This poem written during my dissertation process – looking at the overrepresentation of African American men in the Los Angeles homeless response system:

Oh Great Mother I hear your cries and feel your heaves as you lay down your burden on the river’s edge. Your breasts are no longer filled with the nourishment of milk, but of contaminated blood, shed through the sacrifice of your male child, the pharmako of this society. Your surviving sons are as a lost tribe of Israel, wandering through the desert of life like zombies seeking a sign or symbol to tell them where exactly they belong. As long as they are lost, as their daughter, so am I. Oh great one may you shake the earth with your rhythm so that we feel the beat and dance our way back to home, back to love, back to self.

In his 1956 speech – Birth of a New Nation, Dr. King affirmed “there comes a time when people get tired of being plunged across the abyss of exploitation, where they have experienced the bleakness and madness of despair. There comes a time when people get tired of being pushed out of the glittering sunlight of life’s July and left standing in the pitying state of an Alpine November.

My fellow relations, I believe we are in this time now and have gathered to find a remembering of and creation of a new way of relating to one another – and we must understand how we got here.

From illusion of separation to the practice of love . . .

Prayer to Osun

Osun is the great Mother warrior being of light, an orisa, in the Ifa spiritual tradition. She is a defender of humanity and both reminds and users in our understanding of self-love so that we may share love with one-another.

This is an oriki- a greeting prayer that I would like to offer in this space to open our eyes and hearts to receive.

Osun ni ki baabaa o si

Ko lo ree bole niwajen igi oko

O ni ki baaboo o si

Ko lo ree bo eruwa lo dan

Ki ona oma doju olona ru mo

Oyiya losun fi n ya won loju peregede

Ya mi lo ju n rinu

Oyiya ya mi loju n rina

Ya mi loju n rina raje

Oyiya ya mi loju n rinu

Ya mi loju n rina ri gbogbo ire

Oyiya ya mi loju n rinu

Osun ordered darkness to move

And land in front of forest trees

Osun ordered darkness to move

And land on the grass in grass fields.

Least they miss the path again

It was with comb Osun opened their eyes clearly

Open my eyes to see

Oyiya, open my eyes to see

Open my eyes to see wealth

Oyiya, open my eyes to see

Open my eyes to see all good things

Oyiya, open my eyes to see.

Ifa as an understanding of our times

In troubling times such as these, it is Ifa, my faith, that I turn to for knowledge, wisdom, and understanding – doing my best, but not always doing it right – to not react too soon emotionally or physically to people, words, action I disagree with – but seeking to see deeper what is the need of the universe being asked to be seen in this moment – remembering that even those who cause me harm are a part of the same human family – a form of agape love where wisdom and understanding come together in sweetness.

In Odu Osa Adijo – Ifa says

- Osa take a look

- Iwori take a look

- Whatever we look at together, we will be perfect

- These were Ifa’s declarations for Ologbon (the wise)

- The same was also declared for Imoran (the Knowledgeable)

- They were advised to offer ebo

- They complied

- Both the wise and the knowledgeable

- When they meet each other

- Their matter will be as sweet as honey

Ifa is an old tradition. As a cosmology and culture it survived the period of Enlightenment intact – not undergoing the Carthusian split that separated the European mind from body and opened the portal to colonialism – “I think therefore I am.”

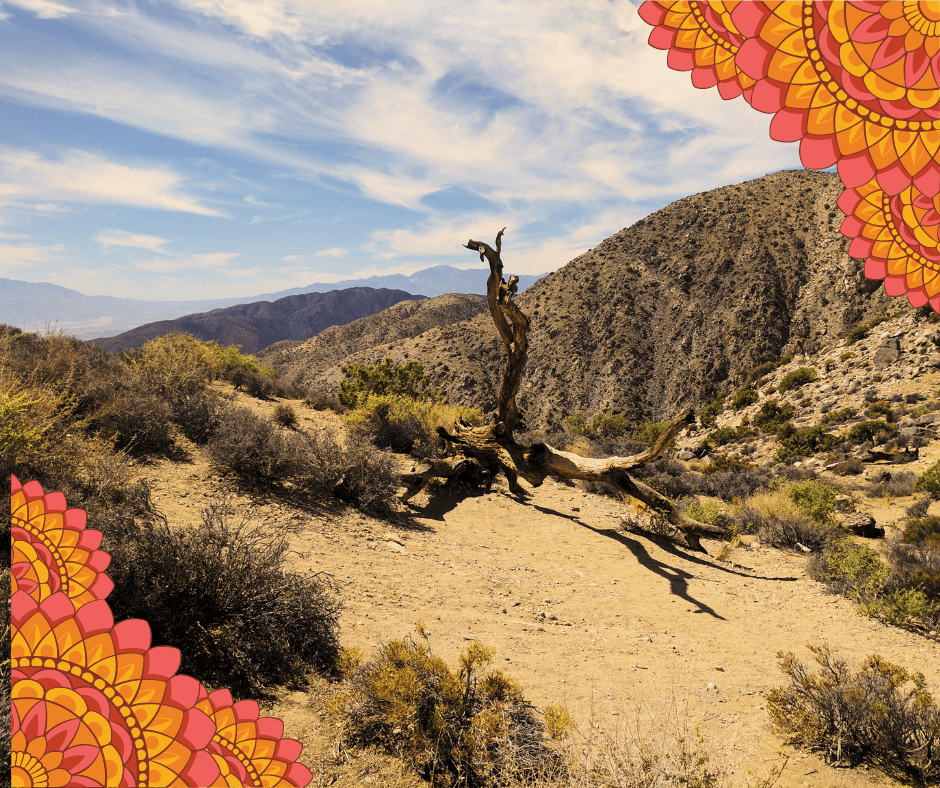

The sacred is amplified throughout the beingness of the world – our interdependent humanity, water ways, mountains, deserts, animals and vegetation.

One aspect of Ifa that I love is as an earth-based tradition, when you read through the Odu, you come to understand that every being has a purpose and was intentionally placed on earth as there are many stories about when a certain plant or animal – as well as not just humans, but all of our body parts – came to earth and reference to their purpose or struggle. In sharing their stories – they also point to the medicine in the interconnectedness.

So how through time and culture have we become so separated when many of our ancient texts give guidance on the interwovenness and sacredness of humanity?

Wendell Berry, a 91 year old white southern man – an author and poet who I met through the late bell hooks, said back in the 1970’s “We are all to some extent the products of our exploitative society, and it would be foolish and self-defeating to pretend that we do not bear its stamp.

He goes on to state how as we advanced into the modern age – we separated from the interconnectedness of our world and into an imaginary fantasy of a sovereign human that could create the world through materialism and technologies where anything could be commodified and transactional with no accountability as even justice could be bought.

As I have reflected on the amplified narcissism of our culture and its embodiment among leaders in many settings today – I think about how we have been hoodwinked – to call in Brother Malcom X – into thinking our worth has been pulled outside of ourselves into these objects we call apps and our value cheapened to the number of likes and the more we leverage this intense longing of connection within to talk at people about everything no longer creating anything and yet we are ‘influencers.”

I think about how many people proudly say how many followers they have, yet do not know the name of their grandmother or great-grandmother – let alone 7 generations back.

Berry -How could we divorce ourselves completely and yet responsibly from the technologies and powers that are destroying our planet? Once our personal connection to what is wrong becomes clear, then we have to choose. We can go on as before, recognizing our dishonesty and living with it the best we can, or we can begin the effort to change the way we think and live.

The late bell hooks in her book All About Love stated – there is a gap between the values they (we) claim to hold and their (our) willingness to do the work of connecting thought and action, theory and practice to realize these values and thus create a more just society.

Coming Back to ourselves

So how then, do we come back to ourselves when not only have we been disconnected for so long – but many of us are disillusioned in thinking we ourselves are whole -pointing fingers at everyone else as the problem referring to this illusion of separation when really, we are part of a whole.

From illusion of separation to the practice of love

Further in Birth of a New Age, Dr. King advised – We must prepare to go into this new age without bitterness. That is a temptation that is a danger to all of those of us who have lived for many years under the yoke of oppression and those of us who have been confronted with injustice, those of us who have lived under the evils of segregation and discrimination, will go into the new age with bitterness and indulging in hate campaigns. We cannot do it that way. For if we do it that way, it will be just a perpetuation of the old way.

Whew – ouch – Dr. King was asking us to reach down into the bellows of the soul – when in these moments of sense making – we are simply seeking to survive. AND, Ifa has helped me understand the call of a new consciousness that is asking to be born.

In the homelessness services sector – a philosophical approach called harm reduction – centers the vision to see that we live in an abundant world where everyone can meet their needs. Shira Hassan in Saving our Own Lives stated – transformation is never a painless process. Along with growth and expansion comes inevitable pain and suffering. But society must break down.

Paulo Freire advised that “liberation is thus a childbirth, and a painful one. The person who emerges is a new person, viable only as the oppressor-oppressed contradiction is superseded by the humanization of all people.

Clearly we are all gathered here for something new to emerge so we must ask ourselves – what is the work that we are doing right now to prepare for the birth of the emergent?

Some day I hope we will sit in dialogue and co-vision our beloved community. Until then, I offer these three steps, a number sacred in Ifa – you, me, and earth as witness – that you can take starting now.

- Apologize to yourself – an act of self-love for all of the ways you have survived the wilderness of modernity – including forging yourself to conform with recognition from dominant society and not attending to the wounds you carry; releasing the shame and stigma that often arises when our value-consciousness meets the authoritarianness of society and we deny our own spiritual, mental, and physical needs and inherent wisdom to fit in.

- Honor your Ancestors – I don’t care if your ancestors owned people or held racists or sexist beliefs or drank too much. No human is all evil or all good. We are humans that have good and bad moments – so can we find the good to honor? Isn’t there someone in your lineage who fought for you? Had a dream for you to be here at this moment? In honoring our Ancestors, we are not calling them from the realm of where they dwell back to the present – yet instead are seeking to shift the wake of their energy left behind on earth so its stagnation does not shapeshift and replicate the harm they may have done on earth.

In honoring our ancestors – include the lands where you were born, lived, and dwell now; include the plants that nourish our souls through their beauty, nourishment, protection, or medicinal properties. Not long ago, a drunk driver veered off the main road onto the front of our property. The ivy in front of both our neighbor’s home and our home slowed her car down, and our walkway railings steered her away from running into my fiance’s home office in the front of our house, where he was up late working. (story of ivy and the drunk driver).

In hooks book on Belonging, she shares stories from her childhood community in Kentucky spoken by the Elders who said their relationship with the earth and attunement to the various cycles of nature – affirmed their belief in a higher power and negated the ideas of supremacy that white people projected onto them during the period of enslavement and beyond. How many of us connect to the earth as teacher for her wisdom gained through the survival of millenia?

- Connect with an Elder – Too many of our Elders are dying with libraries of unshared knowledge because in a capitalist, transactional, exploitative society – we do not value aging. I try once a week to ‘hang out’ with my mother-in-love and her friends. The youngest is around 76. I have learned so much from being quiet in their presence, watching their interaction and seeing the genuine excitement that they share when they see one another. Through them, age is no longer a limiting factor on life – and instead learning the sacred value of relationships as the medicine for long-life. We also must recognize that in some cases, elders will be chronologically younger than us too – out of the mouths of babes.

Do these things. Apologize to yourself, honor your ancestors, connect with an elder – Be unafraid and surrender where the path will then lead you – Carl jung – once said – the known path is dead..

When we heal ourselves – and disrupt the separation within us – we will by universal law change the world.

I end with this final quote from Birth of a Nation – taking license to think about physical segregation as a collective spiritual separation – –

“So that we are not to think that segregation will die without an effort and working against it. Segregation is still a reality in America. We still confront it in the South and it is blaring in conspicuous forms. We still confront it in the North in its hidden and subtle form. But if democracy is to live, segregation must die. Segregation is evil, segregation is against the will of the Almighty God, segregation is opposed to everything that democracy stands for, segregation is nothing but slavery covered up with the niceties of complexities. So we must continue to work against it.”

Thank you for listening.

May the Mothers be pleased with these words and may those inspired to action be supported, and may we all walk out of here in the spirit of love.

Ase, Ase, Ase.